“Are you Robert?” I say as I come in.

“Robert? Robert’s gone, hasn’t he,” he says, addressing two women over my shoulder. I look around in confusion. “I’m only joking,” he says then, “I’m Robert.”

So I meet the Reverend of St Mary’s. It’s a big church, made for a large village in the 14th century, in connection with the local abbey. “It was meant for greater things — this was going to be the local market town, a role instead taken by Baldock.”

The church is made from ‘clunch’ stone, which is unusually soft. The main problem is the tower, which is cordoned off behind a sign that warns of falling masonry. It was rendered in concrete 100 years ago, Robert explains, “they used to think it protected mediaeval buildings”.

Its spire was added in 1415, after Agincourt, to celebrate Henry V’s great victory. “It will not fall down tomorrow, but it has to be fenced off — and it will not get better.”

They are applying for four million pounds from the Lottery. “It would be impossible for a little village like this to raise it from coffee mornings in a century.”

Robert came here as vicar in 2015, although he grew up locally. “My mum still lives in Baldock,” he says, “that was a factor.”

“Ashwell is a very vibrant community,” he says, flicking me through a list of upcoming events in church, inculding the annual music festival. They still have a railway station; a lot of people commute to London. There is a primary school, a butcher and a baker, and three pubs. There are two services most Sundays, total attendance being about 100, which on high days and holidays can go up to 600. They have choir, flower group, Mother’s Union.

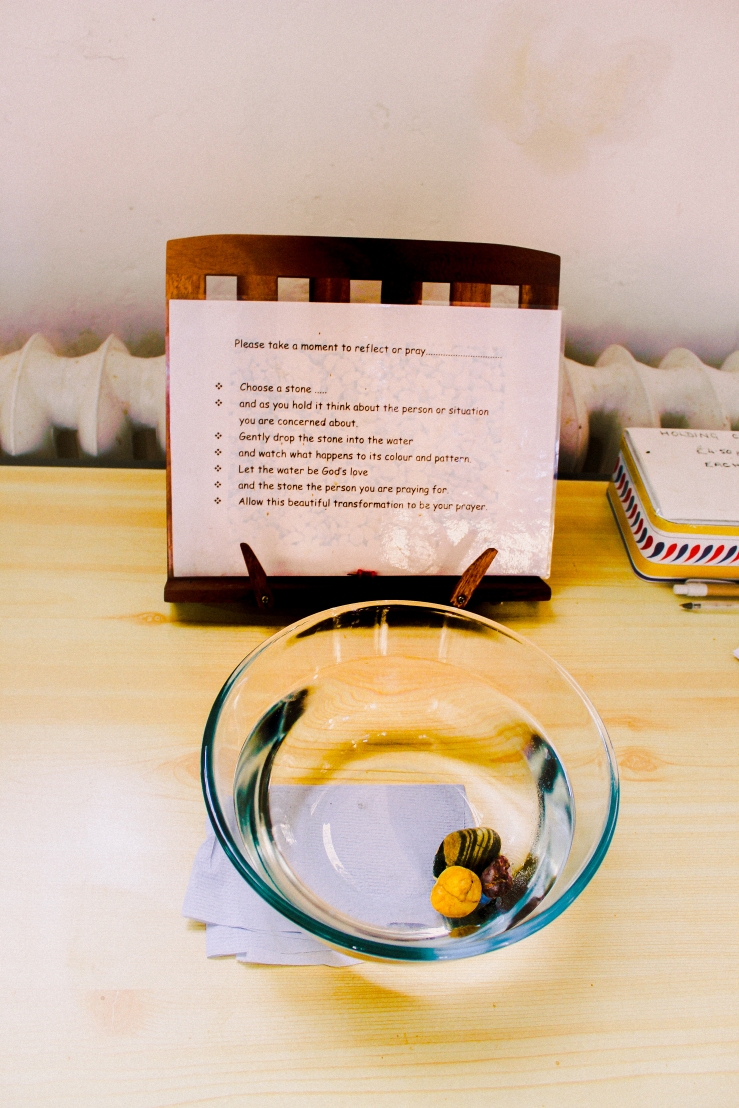

In the corner there is a charity table; a plastic box for food bank donations. Food poverty isn’t a problem in this community. “The collection gets taken to Letchworth,” he says.

The chancel, bare from the Reformation and white in the winter sun, was recently restored. “Most churches pre-Reformation would have had wall paintings,” Robert says. I can trace the remnants of dark twisting paint on the base of some of the columns. There are fragments of recovered mediaeval stained glass in the upper windows.

Over the altar hangs a figure of the Risen Christ by John Mills, a sculptor who lives locally. Christ hovers as if borne up on a current, palms upturned, before the outline of the cross.

In the Lady Chapel is the work of another famous artist, Percy Sheldrick: William Morris’s carpet weaver, whose work is also in Westminster Abbey. He embroidered an altarpiece in memory of his mother who had lived locally. His nephew still lives in the village. The Queen Mother was a fan — she came to see his work on a private visit.

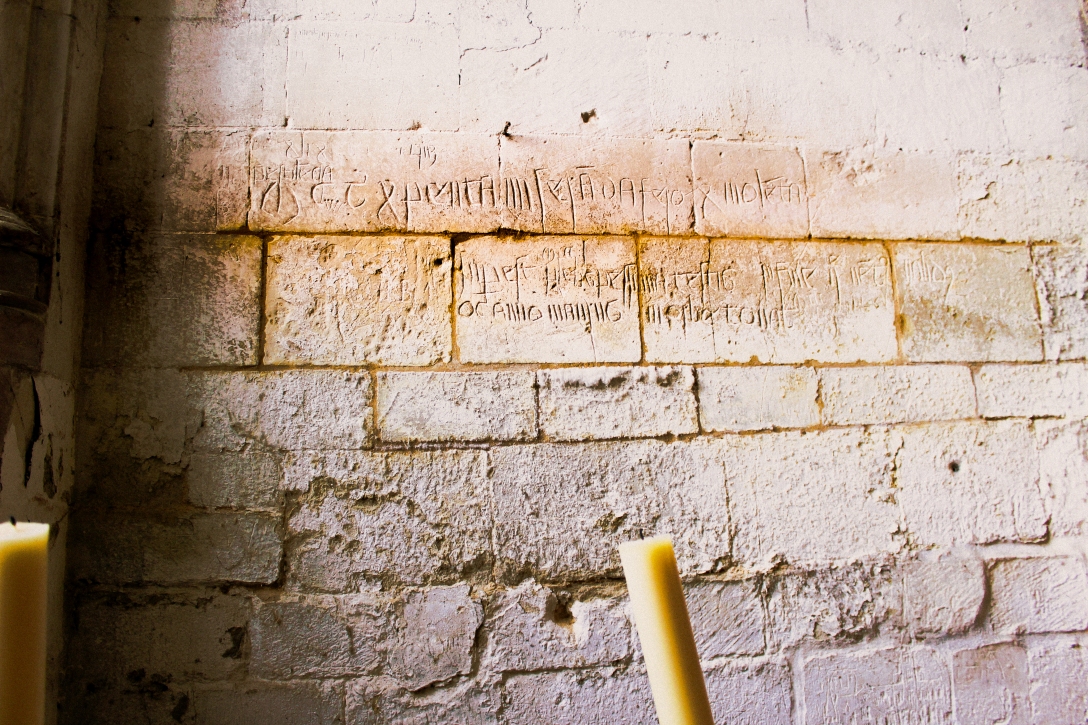

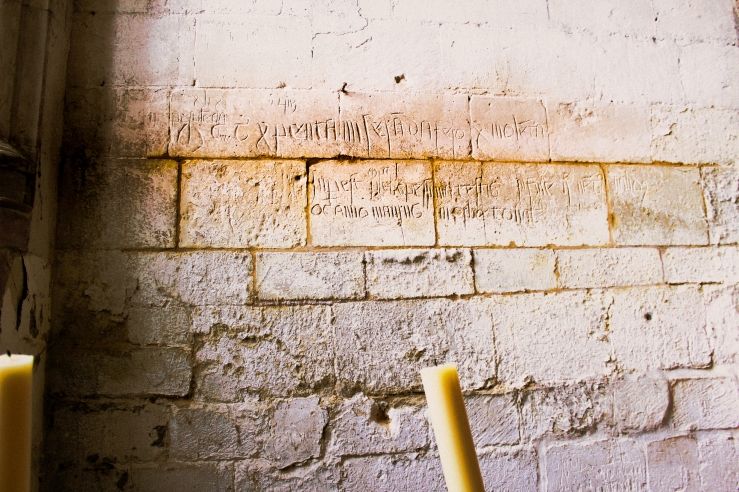

But this church’s most famous works of art are informal: the graffiti scratched into the yielding walls. A scrawled runic sentence in the tower commemorates the Black Death of 1349.

“There was a plague

1000 three times 100, five times 10 a pitiable fierce violent (plague departed)

A wretched populace survives to witness

And in the end a mighty wind Maurus, thunders in this year of the world 1361”

The storm on St Maur’s Day 1361 was so strong it blew down the spire of Norwich Cathedral; it was thought to have extinguished any remains of pestilence in the air.

Further evidence of the plague exists in the form of a suspected plague pit, now guarded by three fat yew trees, next to the churchyard wall.

Further evidence of the plague exists in the form of a suspected plague pit, now guarded by three fat yew trees, next to the churchyard wall.

Below this is a sketch of Old St Paul’s Cathedral, surprisingly accurate, which must have been made between 1360 — when Ashwell tower was built — and 1561 when the spire of Old St Paul’s fell down. Mediaeval drawings of this accuracy are rare, even in manuscript.

There is a sweet smell of cleaning fluid from the ladies dusting with multicoloured wands. After Robert has left, one of them directs me to look at the columns. “Have you seen the graffiti over here?” she says. “I think they did it for when they were inside, for the Black Death.” There are mysterious roundels, possibly mass dials, and outlines of other buildings — churches and castles.

On one column are scratched many names and dates, name over name, grinding deeper the ancient paint, fingers scratching in desperation, a great cloud of spirits, a thousand voices crying down the centuries.